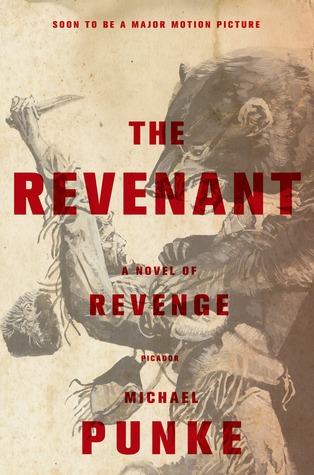

Author: Michael Punke

Rating: 8/10

Last Read: March 2018

I purchased The Revenant a few months ago and experienced a few false starts with it. For some reason, I was never able to make it past the first few pages before deciding to pick another book. During this past attempt, I ended up being engrossed in the book and finished it in two sittings.

The Revenant is set in the 1820s and takes place in the expanding western frontier. The book is based on the life of Hugh Glass, a fur trapper who was mauled by a grizzly and abandoned to die by his companions. He makes his way 200-300 miles back to the nearest settlement to restock so he can get revenge on his former companions who abandoned him to die. Along the way he faces death due to injuries, illness, starvation, predators, and hostile Native Americans.

I recommend The Revenant for those who love the wilderness. It’s also a great read for students of the human soul, as revenge is an interesting and powerful motivation for accomplishing crazy feats. Not a great selection for pre-bed reading, however – there are intense scenes throughout the book.

He vowed to survive, if for no other reason than to visit vengeance on the men who betrayed him.

My Highlights

God had placed him in a garden of infinite bounty, a Land of Goshen in which any man could prosper if only he had the courage and the fortitude to try. Ashley’s weaknesses, which he confessed forthrightly, were simply barriers to be overcome by some creative combination of his strengths. Ashley expected setbacks, but he would not tolerate failure.

In truth, Glass had developed significant doubts about the captain. Misfortune seemed to hang on him like day-before smoke.

I’m glad I don’t have to worry about enemies when I make a fire:

They bled the game, gathered wood, and set two or three small fires in narrow, rectangular pits. Smaller fires produced less smoke than a single conflagration, while also offering more surface for smoking meat and more sources of heat. If enemies did spot them at night, more fires gave the illusion of more men.

He knew that leadership required him to make tough decisions for the good of the brigade. He knew that the frontier respected—required—independence and self-sufficiency above all else. There were no entitlements west of St. Louis. Yet the fierce individuals who comprised his frontier community were bound together by the tight weave of collective responsibility. Though no law was written, there was a crude rule of law, adherence to a covenant that transcended their selfish interests. It was biblical in its depth, and its importance grew with each step into wilderness. When the need arose, a man extended a helping hand to his friends, to his partners, to strangers. In so doing, each knew that his own survival might one day depend upon the reaching grasp of another.

The utility of his code seemed diminished as the captain struggled to apply it to Glass. Haven’t I done my best for him? Tending his wounds, portaging him, waiting respectfully so that he might at least have a civilized burial. Through Henry’s decisions, they had subordinated their collective needs to the needs of one man. It was the right thing to do, but it could not be sustained. Not here.

The human soul can be dark:

Wasn’t that why he was there in the clearing—to salve his wounded pride? Not to take care of another man, but to take care of himself? Wasn’t he just like Fitzgerald, profiting from another man’s misfortune? Say what you would about Fitzgerald, at least he was honest about why he stayed.

The boy came to believe that going west was more than just a fancy for someplace new. He came to see it as a part of his soul, a missing piece that could only be made whole on some far-off mountain or plain.

There is a tide in the affairs of men, Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.

Once focused, it was clear that the eyes stared back with complete lucidity, clear that Glass, like Bridger, had calculated the full meaning of the Indians on the river. Every pore in Bridger’s body seemed to pound with the intensity of the moment, yet to Bridger it seemed that Glass’s eyes conveyed a serene calmness. Understanding? Forgiveness? Or is that just what I want to believe? As the boy stared at Glass, guilt seized him like clenched fangs. What does Glass think? What will the captain think?

The human/snake relationship has always been an interesting one:

Glass wanted to roll away, but there was something inevitable about the way the snake moved. Some part of Glass remembered an admonishment to hold still in the presence of a snake. He froze, as much from hypnosis as from choice. The snake moved to within a few feet of his face and stopped. Glass stared, trying to mimic the serpent’s unblinking stare. He was no match. The snake’s black eyes were as unforgiving as the plague. He watched, mesmerized, as the snake wrapped itself slowly into a perfect coil, its entire body made for the sole purpose of launching forward in attack.

He would crawl until his body could support a crutch. If he only made three miles a day, so be it. Better to have those three miles behind him than ahead. Besides, moving would increase his odds of finding food.

At thirty-six, Glass no longer considered himself a young man. And unlike young men, Glass did not consider himself as someone with nothing to lose. His decision to go west was not rash or forced, but as fully deliberate as any choice in his life. At the same time, he could not explain or articulate his reasons. It was something that he felt more than understood.

In the last moments of daylight he examined the rattles at the tip of the tail. There were ten, one added in each year of the snake’s life. Glass had never seen a snake with ten rattles. A long time, ten years. Glass thought about the snake, surviving, thriving for a decade on the strength of its brutal attributes. And then a single mistake, a moment of exposure in an environment without tolerance, dead and devoured almost before its blood ceased to pump. He cut the rattles from the remains of the snake and fingered them like a rosary. After a while he dropped them into his possibles bag. When he looked at them, he wanted to remember.

The frustrating necessity of delay was like water on the hot iron of his determination—hardening it, making it unmalleable. He vowed to survive, if for no other reason than to visit vengeance on the men who betrayed him.

Still, he thought, there was no luck at all in standing still.

Glass came to visualize his strength as the sand in an hourglass. Minute by minute he felt his vitality ebbing away. Like an hourglass, he knew, a moment would arrive when the last grain of sand would tumble down the aperture, leaving the upper chamber void.

He resolved to stop earlier the next day. Perhaps dig pits in two locations. The thought of slower progress irritated him. How long could he avoid Arikara on the banks of the well-traveled Grand? Don’t do that. Don’t look too far ahead. The goal each day is tomorrow morning.

The wolf waits patiently for a mistake and then strikes. How often do you wait for the right moment before leaping into action?

A hundred yards downstream from Glass, a pack of eight wolves also watched the great bull and the outliers he guarded. The alpha male sat on his haunches near a clump of sage. All afternoon he had waited patiently for the moment that just arrived, the moment when a gap emerged between the outliers and the rest of the herd. A gap. A fatal weakness. The big wolf raised himself suddenly to all fours.

It wasn’t until the wolves began to move that their lethal strength became obvious. The strength was not derivative of muscularity or grace. Rather it flowed from a single-minded intelligence that made their movements deliberate, relentless. The individual animals converged into a lethal unit, cohering in the collective strength of the pack.

The white wolf crouched, poised, it seemed, to attack again. But suddenly the wolf with one ear turned and ran after the pack. The white wolf stopped to contemplate the changing odds. He knew well his place in the pack: Others led and he followed. Others picked out the game to be killed, he helped to run it down. Others ate first, he contented himself with the remainder. The wolf had never seen an animal like the one that appeared today, but he understood precisely where it fit in the pecking order. Another clap of thunder erupted overhead, and the rain began to pour down. The white wolf took one last look at the buffalo, the man, and the smoking sage, then he turned and loped after the others.

The notion of burial had always struck him as stifling and cold. He liked the Indian way better, setting the bodies up high, as if passing them to the heavens.

The Indian accomplished effortlessly what Glass was compelled to pretend—an air of complete confidence. His name was Yellow Horse. He was tall, over six feet, with square shoulders and perfect posture that accentuated a powerful neck and chest. In his tightly braided hair he wore three eagle feathers, notched to signify enemies killed in battle. Two decorative bands ran down the doeskin tunic on his chest. Glass noticed the intricacy of the work, hundreds of interwoven porcupine quills dyed brilliantly in vermillion and indigo.

Lies tend to compound:

“We buried him deep … covered him with enough rock to keep him protected. Truth is, Captain, I wanted to get moving right away—but Bridger said we ought to make a cross for the grave.” Bridger looked up, horrified at this last bit of embellishment. Twenty admiring faces stared back at him, a few nodding in solemn approval. God—not respect! What he had craved was now his, and it was more than he could bear. Whatever the consequences, he had to purge the awful burden of their lie—his lie. He felt Fitzgerald’s icy stare from the corner of his eye. I don’t care. He opened his mouth to speak, but before he could find the right words, Captain Henry said, “I knew you’d pull your weight, Bridger.” More approving nods from the men of the brigade. What have I done? He cast his eyes to the ground.

He felt disdain and even shame for the filthy Indians who camped around the fort, prostituting their wives and daughters for the next drink of whiskey. There was something to fear in an evil that could make men leave their old lives behind and live in such disgrace.

Beyond Fort Brazeau’s effect on the resident Indians, other aspects of the post left him profoundly disquieted. He marveled at the intricacy and quality of the goods produced by the whites, from their guns and axes to their fine cloth and needles. Yet he also felt a lurking trepidation about a people who could make such things, harnessing powers that he did not understand. And what about the stories of the whites’ great villages in the East, villages with people as numerous as the buffalo. He doubted these stories could be true, though each year the trickle of traders increased.

Standing to greet another, a sign of respect:

Yellow Horse stood when Glass walked into the camp, a low fire illuminating their faces.

Again, standing to greet:

Dominique rose, shook Glass’s hand and said, “Enchanté.”

My kit doesn’t look anything like this:

They returned to the cabin and Glass picked out the rest of his supplies. He chose a .53 pistol to complement the rifle. A ball mold, lead, powder, and flints. A tomahawk and a large skinning knife. A thick leather belt to hold his weapons. Two red cotton shirts to wear beneath the doeskin tunic. A large Hudson’s Bay capote. A wool cap and mittens. Five pounds of salt and three pigtails of tobacco. Needle and thread. Cordage. To carry his newfound bounty, he picked a fringed leather possibles bag with intricate quill beading. He noticed that the voyageurs all wore small sacks at the waist for their pipe and tobacco. He took one of those too, a handy spot for his new flint and steel.

Kiowa laughed too, then said: “With all due respect, mon ami, your face tells a story by itself—but we’d like to hear the particulars.

Kiowa understood early in his career that his trade dealt not only in goods, but also in information. People came to his trading post not just for the things they could buy, but also for the things they could learn.

Glass shook his head again, more firmly this time. “I have my own affairs to attend.” m

“Bit of a silly venture, isn’t it? For a man of your skills? Traipsing across Louisiana in the dead of winter. Chase down your betrayers in the spring, if you’re still inclined.”

The warmth of the earlier conversation seemed to drain from the room, as if a door had been opened on a frigid winter day. Glass’s eyes flashed and Kiowa regretted immediately his comment. “It’s not an issue on which I asked your counsel.”

“No, monsieur. No, it was not.”

The colder weather settled into Glass’s wounds the way a storm creeps its way up a mountain valley.

With the exception of Charbonneau, who was gloomy as January rain, the voyageurs approached each waking moment with an infallibly cloudless optimism. They laughed at the slimmest opportunity. They showed little tolerance for silence, filling the day with unceasing and passionate discussion of women, water, and wild Indians. They fired constant insults back and forth. Indeed, to pass up an opportunity for a good joke was viewed as a character flaw, a sign of weakness. Glass wished he understood more French, if only for the entertainment value of following the banter that kept them all so jolly.

In the rare moments when conversation lagged, someone would break out in zestful song, an instant cue for the others to join in. What they lacked in musical ability, they compensated in unbridled enthusiasm. All in all, thought Glass, an agreeable way of life.

Like many of the things he encountered each day, Professeur was confused by what happened next. He felt an odd sensation and looked down to find the shaft of an arrow protruding from his stomach. For a moment he wondered if La Vierge had played some kind of joke. Then a second arrow appeared, then a third. Professeur stared in horrified fascination at the feathers on the slender shafts. Suddenly he could not feel his legs and he realized he was falling backward. He heard his body make heavy contact with the frozen ground. In the brief moments before he died, he wondered, Why doesn’t it hurt?

His awe of the mountains grew in the days that followed, as the Yellowstone River led him nearer and nearer. Their great mass was a marker, a benchmark fixed against time itself. Others might feel disquiet at the notion of something so much larger than themselves. But for Glass, there was a sense of sacrament that flowed from the mountains like a font, an immortality that made his quotidian pains seem inconsequential. And so he walked, day after day, toward the mountains at the end of the plain.

Henry was a failure at many things, but he understood the power of incentives.

Stunned silence filled the room as the men struggled to comprehend the vision before them. Unlike the others, Bridger understood instantly. In his mind he had seen this vision before. His guilt swelled up, churning like a paddle wheel in his stomach. He wanted desperately to flee. How do you escape something that comes from inside? The revenant, he knew, searched for him.

Glass reached down and removed the small pouch that Pig wore around his throat. He dumped the contents onto the ground. A flint and steel tumbled out, along with several musket balls, patches—and a delicate pewter bracelet. It struck Glass as an odd possession for the giant man. What story connected the dainty trinket to Pig? A dead mother? A sweetheart left behind? They would never know, and the finality of the mystery filled Glass with melancholy thoughts of his own souvenirs.

I also dislike someone who complains about problems but offers no solutions:

Glass shot an irritated glance at Red, who had an uncanny knack for spotting problems and an utter inability for crafting solutions. That said, he was probably right. The few creeks they’d passed had been small. Any Indians in the area would hug tight to the Platte, directly in their path. But what choice do we have?

Kiowa said, “I’m sorry that you never had a proper rendezvous with Fitzgerald. But you should have figured out by now that things aren’t always so tidy.”

They stood there for a while, with no sound but the flapping of the flag. “It’s not that simple, Kiowa.”

“Of course it’s not simple. Who said it was simple? But you know what? Lots of loose ends don’t ever get tied up. Play the hand you’re dealt. Move on.”

Glass said nothing more. Kiowa too was silent for a long time. Finally he said quietly, “Il n’est pire sourd que celui qui ne veut pas entendre. Do you know what that means?”

Glass shook his head.

“It means there are none so deaf as those that will not hear. Why did you come to the frontier?” demanded Kiowa. “To track down a common thief? To revel in a moment’s revenge? I thought there was more to you than that.”

He stood there on the high rampart for a long time that night, listening to the Missouri and staring at the stars. He wondered at the source of the waters, of the mighty Big Horns whose tops he had seen but never touched. He wondered at the stars and the heavens, comforted by their vastness against his own small place in the world. Finally he climbed down from the ramparts and went inside, quickly finding the sleep that had eluded him before.

Buy the Book

If you are interested in purchasing this book, you can support the website by using our Amazon affiliate link: